Two kinds of pattern matching

There are two kinds of... well, actually no. In basically anything outside of mathematics, things are rearely (if ever) either-or. Or if they are, then the division might be very unhelpful or even useless. (There's a mathematical anecdote, sometimes attributed to John von Neumann, that "Classifying mathematical problems to linear and non-linear is like classifying the universe into bananas and non-bananas." So yes, a binary division might exists, but it wouldn't serve a cognitive purpose.)

Let's try again. There are many kinds of things, possible an unlimited amount of kinds of things. And this division into kinds of things might or might not be overlapping, shades of each other or gradients. They might or might not cover all the cases we are interested in. Well. That sounds closer to truth, though to me it still feels a bit specific and rigid when compared to the universe at large. But it's at the same time too vague for me to find any use in.

So fuck all that. Today we will look at two types of things. We do not claim anything about the relations of these types of things - they might be distinct, complementary, correlated, or "the same guy wearing different sweatpants" as you say. Or it might be that the whole concept of attempting to classify their interrelations is both arrogant and ill-defined. But we don't care for now. We will look at two things that might or might not be separate or even exist - so instead of a "two" there might need to be "zero", "one", "fifteen" or "NaN". But gritting my teeth I now say that we will look at two ways how one might try to infer patterns in things.

Fitting a pattern into data

Sometimes we do pattern matching by connecting stars of the night sky into something we call "The Big Dipper" or "Orion". This is not a lie. The stars exist, and the naming of such patterns provides a way for us to convey information: "Tonight Jupiter will be visible near the big dipper's handle." But the big dipper is more akin to the concept of Tuesday than the concept of addition. The big dipper only exists as an emergent object in the space of human interaction. Both because of how we happen to see 3D star combinations as projections to our earthly 2D sky in this particular space, but also on how we as humans in the night happen to end up finding meanings in these essentially random patterns.

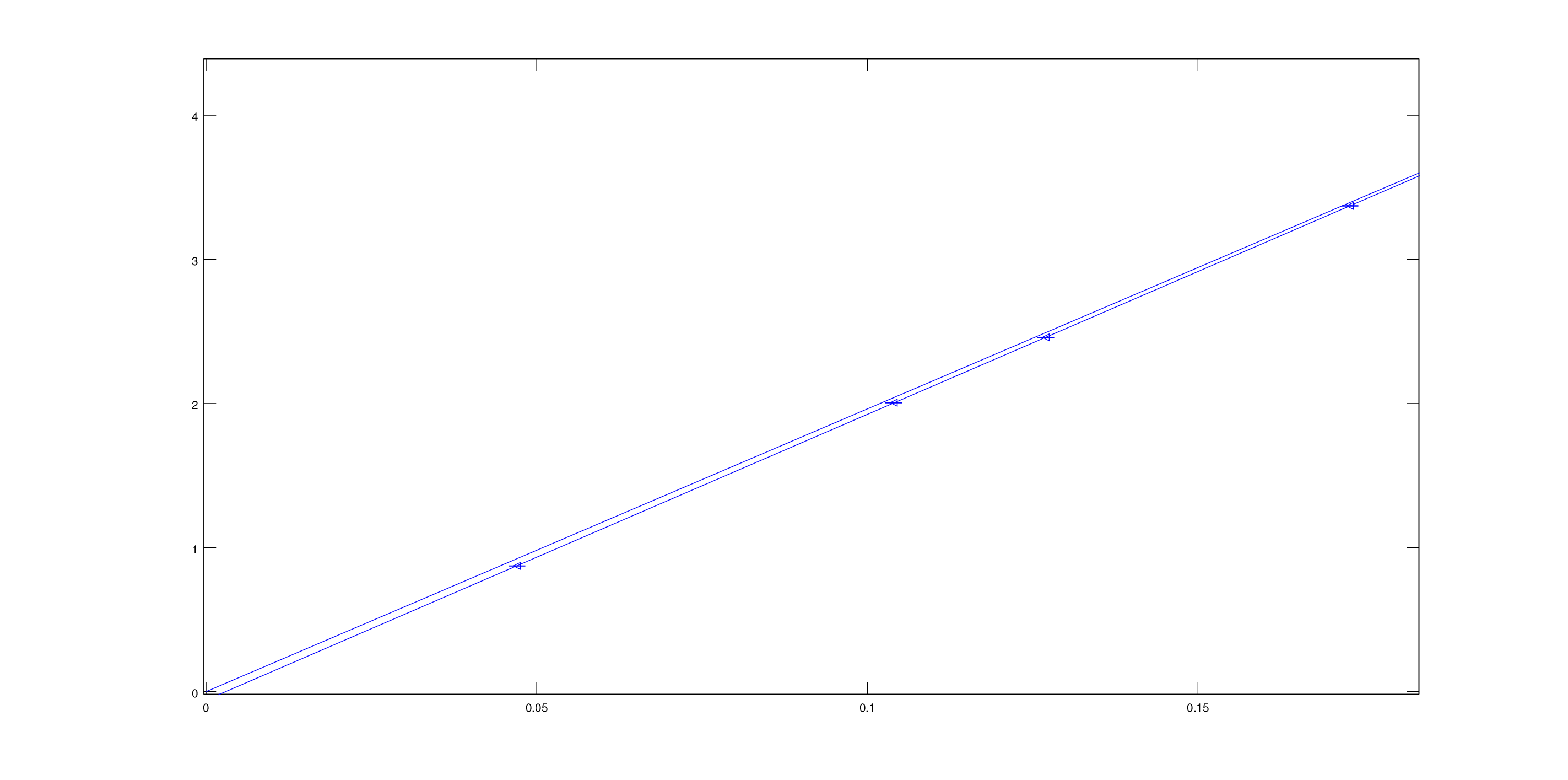

On the other hand, on the rare event when I do something like laboratory measurements, I might try to connect dots with a line like this:1

And in this situation I fit a line to points and do assume that there is more to the line than just me making it up as a social convention. I implicitly assume there is some actual structure. Some rule of physics or an aspect of nature that is independent of me. 2 Some universality that would guarantee that other people chasing the same truths would end up with mostly similar lines.

So these are "the" two kinds of things. Patterns we draw in stars, and patterns we draw in measurement points from a physics lab.

I like both of these kinds of things

As I've said, I really like science. Especially the scientific method, and the universality of truths you might discover. (Though, as a mathematician, I do feel that the universality is to a lesser degree when the truth is found from data and not from a proof.) But I also love connecting points in stars, as you might guess if you read my Dwarf Fortress fanfiction math paper or if you're fluent enough3 in Finnish to read my analysis of a Finnish children's song.

So, What's my point? Again, I don't really know. After writing the aforementioned very long pareiodolic analysis of the Finnish childrens' song my wife asked me, very reasonably, "why?". And I couldn't really give a good answer.4 And I started to wonder if I maybe like it because creating it was such an antithesis to my normal scientific pattern matching? So this text is mostly me trying to verbalize some thoughts on the topic.

Knowing myself, I also rarely do anything that doesn't serve some purpose in some weird optimization strategy. I like many different things, but have time for only a limited amount of them. And I often choose a set things or skills that give each other boosts in some way. This is both a good and a bad thing. On the one hand the interboosting of skillsets gives rise to superlinear possibilities. On the other hand it does also very easily make me drift into the realm of trying to overachieve and burn myself out in forgetting to relax and do things purely for fun. Anyway. What's my ulterior internal motivation for liking to do this kind of pareiodolic pattern matching?

I think that here the reason arises from the feeling that this is good general practice for creativity in finding patterns. It felt like streching my brain when I was doing it. This feeling actually resonated with an interesting article by Keith Sawyer I came across while writing5 this piece. There, in short, the author discusses the idea that creativity is strongly tied to the capability (or possibility?) of coming across very different ideas and creating connections between them.6 So maybe I've instinctively felt that this might be good for creativity? One of my favorite things is when I figure out something clever, especially if it is an "out-of-the-box" style of solution to something.

I would love to claim that this is the reason and that it works, but alas I am not Keith Sawyer. I don't have the backing of expertise for claiming that there is some truth in here, and I would be just naming star patterns. But it is fun to do. And that's enough at least for now.

-

This is from a report in an "introduction to physics - lab 101" type of course. We were trying to measure

g, i.e. the gravity of earth. (We got it to 9.91 +- 0.5 m/s^2.) ↩ -

Here I wish to emphasize that I am writing from a very biased point of view with a strongly science-based worldview. I set this kind of human-independent truth on a much higher pedestal than human-dependent things. But I feel that this is a bad bias. They are different kinds of things, and I do claim that it is good to understand and appreciate their difference. But thinking one as the superior one should not be obvious. Could it be tested? Is this another biased approach? Should it be tested? Is the whole test term loaded? ↩

-

If you are not, then just go and read Unsong by Scott Alexander, and imagine that someone tried to emulate Aaron Smith-Teller's texts with vastly lesser skills. ↩

-

Or, at least anything but the copout answer of "it was fun?". ↩

-

My pace of writing blog-posts is quite erratic. This post has been in the making for about a month, with me writing and editing it in bursts. It does mean that my posting schedule is very irregular, but the good side is that I tend to come across many interesting related ideas while writing on a topic. ↩

-

This seems somehow similar to the old mathematicians' saying that: "Good mathematicians find analogies between things, great mathematicians find analogies between analogies." ↩